Anyone tasked with updating their company website will recognise the numerous problems that come with writing case histories.

There are your best case histories from five years ago, whose important features now look stale or no longer relevant to the problems of today.

Then there are other case histories which while showing brilliance on the part of your organisation remain so classified and secret you can’t breathe a word of the brilliance to anyone.

And there are still more case histories which while very good are quite incomplete or partial. Somehow telling them seems to feel like the story ended too soon, or started too late or other players did the important chunks of it and thereby stole the thunder.

It’s often very difficult to curate a decent show from what’s left, after you’ve culled the ones that won’t see the light of day. The result is many case histories become short and inconclusive; others are hard to follow, and leave a reader, or new business prospect, none the wiser.

So how do you create convincing, engaging case histories that don’t drop anyone in it and feel like they belong to today?

Write 3 seperate drafts

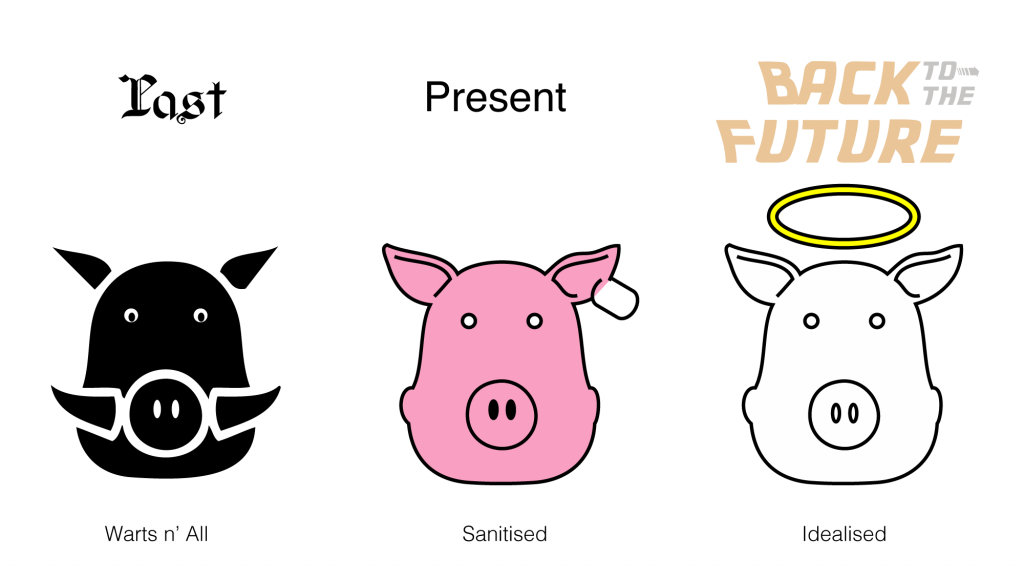

One really simple approach is to split the task into two or three clear and distinct phases, each of which needs its own mind-set.

The first mindset you’ll need is an investigative historian or journalist.

Use this to write a Warts-and-All version first, on the sacred internal understanding that you’re showing it to absolutely no-one externally. But get a case or set of cases written so they’re clear, readable and true without having to worry about other considerations. If necessary, interview the people involved with a tape recorder so you can fully concentrate on what they’re telling you and ask questions that probe what really happened.

Then, when that’s done change your hat to that of a doctor; rewrite your Warts and All text as a sanitised version.

Change the client names, the product names, the industries.

No confidences betrayed, no clients made to look stupid. Transforming it in that way isn’t always a straightforward task but it’s much easier to do when you’re at least clear about what actually happened.

After you’ve written the sanitised version you are free to go one step further.

The hat you need now is a dramatist and or teacher.

You can work backwards from what clients have started to ask the business for. This is the idealised version where you combine different elements of cases that you’ve successfully managed in the past and bring them together so demonstrate solving the problems of today.

Make up the presenting problem, roll two elements from different cases into one, exclude confusing subplots, streamline the story. Do what ever it takes so the story while not literally true is authentic. You may need to write a disclaimer for this, but your audience will usually understand this automatically anyway, just from the genre.

There may never have been a case exactly like this but all the essential features are your company’s bread and butter. The fluency with which you describe the cases communicates your mastery over all the issues, and that’s the real point of the writing.

You will need to give yourself some creative licence to do this, but it’s a good way of showing just how much knowledge your organisation really holds.

When you’ve finished this not only will you have a valuable new business tool for future business, it will also serve to educate new people starting today the triumphs of the past.