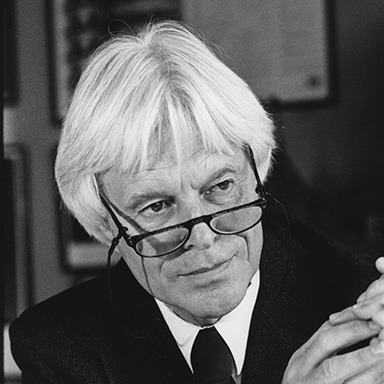

David Abbott was easily the boss I found the most inspiring. When he died, I managed to get my hands on the text of the farewell speech he’d given fifteen years earlier upon his retirement, and which I and the rest of his agency had watched through watery eyes. I remembered the last parts of the speech, about the African storyteller, verbatim.

David Abbott was easily the boss I found the most inspiring. When he died, I managed to get my hands on the text of the farewell speech he’d given fifteen years earlier upon his retirement, and which I and the rest of his agency had watched through watery eyes. I remembered the last parts of the speech, about the African storyteller, verbatim.The speech as a whole combined the acknowledgements of a departing CEO, a little foundational history, and some of what would now be called key values and behaviours going forwards; except of course he would never have allowed himself such buzzwords.

It was a stirring, emotional twenty minutes, and culminated with just a hint of physical ritual invoked from storytellers of a very different culture. Like all his copy it had an strong uplifting ending. What better way to say goodbye?

(Clapping as he takes the podium)

“Thank you. Running into such kindness is a bit like running into a brick wall. It knocks the wind out of you and leaves you speechless.

Lucky then, that I have one with me that I prepared earlier. I only hope I have the composure to get through it.

There are some people in this room who know me very well – and yet have still decided to turn up.

I thank them.

There are many here who know me quite well.

There are others who know who I am, but look at their feet when I get in the lift with them.

Then there are Louise, James, Paul, Justin, Becky, Matthew and Lucy – the new graduate trainees who are not yet quite sure whether I’m Peter Mead or Adrian Vickers.

Dear graduates, this must be a bizarre evening for you and I’m sorry that we overlap by only a week.

You have arrived at a mature, fully formed agency, so you’ll be surprised to hear that we were once an agency where everyone had to work far too hard trying to satisfy difficult clients and management’s outrageous targets.

How times change.

You’ll be surprised to learn, too, that in AMV’s first year the total billings were less than the price of Peter Mead’s latest car. (Perhaps you won’t be surprised to learn that.)

But don’t let’s start at the beginning, let’s start before the beginning.

It is 21 years since Peter and Adrian persuaded me to join them.

Their seduction technique, I later realised was one that they had honed on various girlfriends. It was a two-pronged attack and consisted of a relentless succession of Indian meals and a steady flow of lies and half-truths.

“Our clients are secure,” they said. “You’ll be joining a happy family,” they said. “Financially, we’re more than stable.”

Something must have alerted me because I turned them down and in doing so sealed my fate.

I don’t know if I ever told Peter this before, but it was the grace with which he accepted my refusal that made me change my mind.

“Here is a man,” I thought, “whom I would be happy to have beside me in bad times.”

If you’re looking for incidental wisdom in these words of mine tonight, perhaps there is something here. Perhaps we most accurately define ourselves when things are going against us.

All I know is that if things were ever going to get tough, Peter is the kind of man who would immediately trade down to a Porsche or a Ferrari.

I jest, of course – in the long tradition of joshing and teasing that has marked our friendship and that has fooled no-one.

Adrian, Peter and I have transparently loved each other and looked after each other through all the years.

And this, above all, has made us the kind of agency we are.

And then came Michael (Baulk). Double-breasted, fast talking, his semaphore hands sometimes caressing, sometimes slicing the air to add weight to his words – he brought order and discipline to our affairs.

Somehow he made company growth and personal restraint a desirable banded offer.

On the drive to and from Wentworth mansion he practiced the mantra that saw us throught the 89-93 recession, “Of course it hurts but we’re all in the same boat.”

Old-timers here will recognise earlier hymns to Michael and such jibes are the fate of those whom we ask to chase the income and watch the overheads for us.

But in truth, that was never the real story of Michael. He is more architect than accountant and deserves to be the fourth name on our notepaper.

Some of you will know that we once offered to put his name there, but he declined. “You are the brand,” he said, “you started the agency.” That may be true, but in my mind Michael’s name is above the door, anyhow.

We are three who became four – I feel no less for him than I do for Peter and Adrian – he is a man with a good brain and a good heart. Look after him, I urge you.

Now, where do I go from here? I could haltingly run down the phone list and stop at scores of names who are special to me; but it would be a long night if I did. Some of those people I paid tribute to at a creative lunch last week – including my dear friend and partner, Ron.

Over the next two days I hope to say in private to many of you what there isn’t time to say in public but it wouldn’t be right if I didn’t pick out a couple of names tonight.

First, there is Angela (Porteous), formidable gate-keeper and extraordinary friend.

My children blame Angela for the fact that I have never used a cashpoint, don’t know their phone numbers and can’t work a PC. If all this makes me seem pretty feeble, I plead guilty.

All I know is that Angela and I have been a wonderful team and somehow, between us, we’ve shifted a great deal of work together. I thank her from the bottom of my heart and rejoice in the fact that she is still going to be around to help me in my new life, even though she remains at the agency.

And, of course, I should mention Mr. (Jeremy) Miles. Despite the vast difference in our ages, Jeremy and I have become friends, cricketing companions and, if it’s not too painful a word right now, ‘confidants’.

There haven’t been many days in the 18 years when we haven’t sat down for a chat – and through Sainsbury’s, BT and The Economist there haven’t been many days when we haven’t been in the trenches together, either. He is everything you could wish for in a friend, steadfast, cheerful, loyal, funny, generous.

Andrew (Robertson) and Peter Souter are next on my list. As I’ve stepped down progressively over the past 3 years their sensitivity and kindness to me has made the process bearable. It wasn’t easy to let go, but they in the best traditions of the agency have continued to involve me, treating me with tact, understanding and affection. I hope they know that I return that affection in full.

Finally, I would like to thank Terry Green (organiser of the company cars) who over the years has aided and abetted me in my ambition never to see an MOT certificate. Thank you, Terry. I can’t promise that you’ve heard the last of me.

So, here I am – about to leave not just an agency, but an industry that has supported me, entertained me and stimulated me for 40 years. I have truly been a lucky man.

If I could still remember things, I’m sure I’d have some wonderful memories. You know, the cliche is true, I often remember the distant past more clearly than the recent past – so let’s start there – in the distant past.

The first great hero of mine was David Ogilvy and I saw him for the first time in the early sixties.

I was a junior copywriter at Mather & Crowther and David had just merged our agency with Bensons. The combined workforce was summoned to the Connaught Rooms to hear a pep-talk from our new leader.

He spoke to us in shirt sleeves, red braces brilliantly visible even from the back of the hall where I stood with the rest of the small fry. He was informal and inspiring. Soon after, we received his written wisdom, too: a blue-covered manual called “Observations” – it became my first advertising bible and I never really escaped its strictures.

For the next 40 years I felt guilty if I couldn’t get the client’s name into the headline, and I could never write long copy without putting in crossheads. Why there is a Lord Saatchi and David remains a Mr. seems to me to be one of life’s more inexplicable mysteries.

Another distant scene pops into my head. In July of 1966, I flew to New York with Eve (his wife), who was six months’ pregnant, and Jenny and Matthew who were both under three.

DDB had sent me to New York to be groomed to take over as Creative Director in London when John Withers returned to the States. The process was meant to take six months, though we ended up staying nearly a year.

We travelled on a Friday and arrived in the middle of a New York heatwave. We were booked into a small service apartment in the Gramercy Park Hotel – on the sixth floor with a single air-conditioning unit that made a great deal of noise but no cool air.

On Monday morning I walked the 20 blocks to the office, leaving Eve and the kids behind in a sweltering hotel room in a strange city. What were they going to do all day? How was Eve going to cope. I walked to the office crying, although it was so hot my tears passed for perspiration. (At this point, David had to pause for a moment. 300 of us watched as he seemed overwhelmed by this recollection.)

Of course, it got better. In six weeks we’d found a flat, in November we’d had our second son, Dominic, and I got to know Bill Bernbach.

Bill Bernbach was the most persuasive man I ever met in advertising. His voice was soft but emphatic and when he sat at the boardroom table his small hands would delicately underline the point he was making.

He had the authority of a college professor and the showreel of a genius. I sat mesmerised – how could any client resist him? Most of them didn’t.

When I became MD of DDB’s London office in the late sixties, I would arrange a lunch party whenever Bill was in town. A few of us would sit down with him to eat and talk about advertising.

On one occasion I referred to the agency as Doyle Dane – a common abbreviation at the time. Bill gripped my arm – Doyle Dane Bernbach he said gently as his fingers tightened.

It was a courtesy he richly deserved, though I was surprised he insisted on it – perhaps he was teasing me. perhaps there’s a lesson there – never underestimate the vanity of an agency owner.

One more memory. I have a Polaroid somewhere, taken on my first day at AMV – we were in our little offices in Bruton Place – Ron took the picture. I am in my overcoat, viewed from the back, round shouldered as I fill the kettle from a tap that for some reason is high on the flaky, plastered wall, 3 foot from the sink which is out of shot.

It is a photograph of a refugee in a halfway house, the saddest, most melancholy photograph I’ve ever seen and it almost certainly reflected the way Ron and I felt that day. And yet, look what happened later.

And now I’m saying goodbye in the good times and some of you may be wondering why. Let me try and explain.

I always promised myself I’d do something different before I was sixty and I’m making it by two days.

I like to think it’s a happy omen that I am leaving the agency, as near as dammit, on its 21st birthday.

My own 21st was on October 11th, 1959 and it wasn’t a great time for me – my father had died in June and I was about to go back for what I knew would be a futile last term at Oxford, before I took over the running of my father’s shop.

I went to the pub that night with some friends and at turning-out time I went on to a coffee bar with one of them – really just to delay going home.

We walked in and my friend stopped at a table where he knew one of the girls. One of her friends was Eve and she says that she wanted to marry me there and then. I just knew that I wanted to see her again, which proves just how much smarter woman are than men and how much more determined.

In a very real way on that 21st birthday I got the key to my future, so I’m hoping that this 21st will be lucky, too.

I want to try and write fiction of some kind; maybe I’ll write jokes, maybe I’ll write about gardening, maybe I’ll write scripts. I want to spend more time in my garden, more time with my children and grand-children, more time traveling, more time doing things I don’t even know about yet. But no, I don’t believe I’ve written my last ad for AMV.

I’ve found this a very difficult speech to write – I suspect it shows. I’ve felt the burden of your expectations – I felt you wanted the speech of a lifetime – quite literally – that you wanted me to plunder the past 40 years and come up with gold – golden advice, a set of bliefs and canons that would keep the agency the way it is, protect it in the future. And for some reason I haven’t wanted to do that – I’ve done it before so why not now?

Perhaps this explains it:

When I say good bye to my children I give them a hug and a kiss and say: “See you soon.”

I don’t say “And here are a few tips and principles to help you get through to Thursday.” I just give them a hug and a kiss.

If I were a giant I would cross the road and put my arms around the building opposite (he was giving the speech in the Landmark Hotel, across the road from AMV) and say “Goodbye, see you soon.”

I hope to do just that to many of you, too. It doesn’t seem the time for a lecture and anyhow you all know how to run a great agency.

You care about two things. You care about quality – in everything you do. From the chairs in Reception, to the way you answer a phone, to a piece of Typography, to the ideas you have, to the research you put your name to, to the meetings you hold, to the way you hang a picture, to the way you crop a photograph or write a line.

Quality is always possible and always under threat, but if you don’t seek and defend it you won’t be satisfied and you won’t be happy.

The second thing you must care about? That’s easy. It’s each other.

Take care of each other and nearly everything else will take care of itself. It’s pat, but it’s true.

Both these things take effort and boldness. I’m retiring now because I want to take charge of my future – however long or short it may be – I don’t want to be passive and let the future happen to me – what I’m doing is risky, I could be very lonely in my little office, I know I will miss you, I will miss the fun and the talk. I’m giving up something I’m good at to try something I’ve never tried – I’m going from guru to novice, from safe to uncertain. And I’m happy.

A few months ago I read Peter Brook’s memoirs. I’d like to end by quoting something from his book.

“At any moment we can find a new beginning. A beginning has the purity of innocence and the unqualified freedom of the beginner’s mind.

Development is more difficult, for the parasites, the confusions, the complications and the excuses of the world swarm in when innocence gives way to experience.

Ending is hardest of all, yet letting go gives the only true taste of freedom. Then the end becomes the beginning once more and life has the last word.”

That is how I feel.

In an African village when the storyteller comes to the end of his tale, he places the palm of his hand on the ground and says: “I put down my story here.”

Then he adds, “So that someone else may take it up another day.”

I’ve been privileged to help write the first few chapters of AMV – you will write the next few – it wont be my story, but it will be a good one.

And so I place my palm on the ground – AMV will be fine, you will be fine. “Courage, mon brave,” as Jeremy would say. God bless you all.”