Case history.

After the passion blurb, try doing the case history. If you know the answer to these numbered lines you can save buckets of time and money.

- All stories start with a client who lived in a castle.

- One day something happened that meant they needed to act.

- They came to you.

- You listened to them from a certain discipline or set of distinctions.

- You took them to a place they’d never been.

- They discovered more opportunity there than they expected.

- They lived happily ever after.

The best case histories demonstrate how you used your value proposition to get them from step 4 to 5. This is a fictitious case history but it shows you the idea.

We were first approached by John Smith in the spring of 2015 and he asked us to mow his lawn.

John Smith had a vast lawn but much of the grass was patchy with extensive areas of weed.

We did an initial assessment and came to the conclusion that before we could mow it, parts of the lawn would need re-sowing.

We agreed a sowing fee and within a week both the sowing and the mowing tasks were complete.

By the summer John had a strong, healthy lawn, and decided to host his first garden party for a very long time.

He now saves over a thousand pounds a year by hosting parties in his garden rather than rented venues.

We have since created a gazebo on the front lawn and are helping him with a project to become largely self-sufficient in growing his own vegetables.

In the example above, patchiness is a distinction that wasn’t in the conversation before the expert made the client aware of it. Can you also see how there’s a hidden opportunity in the project, ie. enjoying your lawn with paybacks that more than pay the cost of the project?

Case histories can be much more powerful than just testimonials because the best ones have some transformative quality.

Process.

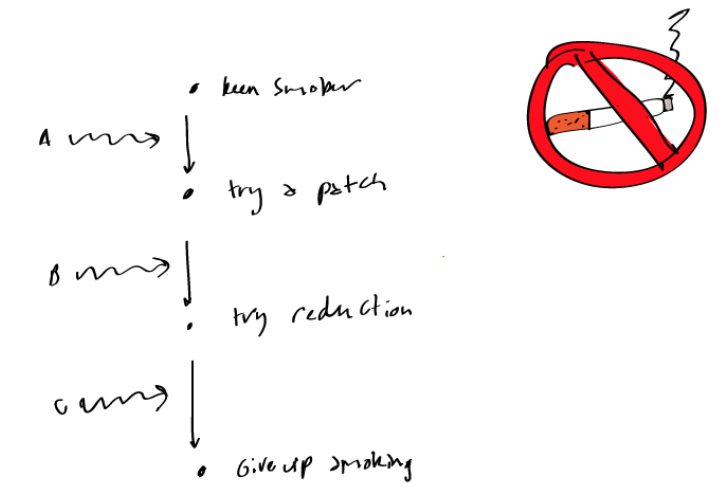

Your process should show how you could take a typical client or prospect from step 3 in a typical case history to step 5. There may be up to several sub steps in your process 3 to 5. It’s a safe bet that there are more steps and more quality going in than you currently believe or know about.

When a client knows your process, it will help alleviate fears that you’ll be taking them for a ride. Complex and new services may have many steps which are unfamiliar to your target audience. Below is the process for a communications organization and you could write an informative paragraph on each step.