It’s hard to do marketing without thinking everything is so different from when we all came into the industry. Even if you’ve only been in the industry for a year or so, you’ve probably noticed some big shifts already. But as ever there’s a counter view, and one provide by the father of advertising, the late, very great Bill Bernbach.

It’s hard to do marketing without thinking everything is so different from when we all came into the industry. Even if you’ve only been in the industry for a year or so, you’ve probably noticed some big shifts already. But as ever there’s a counter view, and one provide by the father of advertising, the late, very great Bill Bernbach.

“It took millions of years for man’s instincts to develop. It will take millions more for them to even vary. It is fashionable to talk about changing man. A communicator must be concerned with unchanging man, with his obsessive drive to survive, to be admired, to succeed, to love, to take care of his own.” Bill Bernbach

*With thanks to Rory Sutherland for reminding us of this quote.

One of the classic B2B ads of Bernbachs era, printed in 1958 is by McGraw Hill publishing. It runs as follows.

So how might it read today? Here’s a guess.

The man sitting in the chair would also nowadays probably be sporting a beard and a mobile device, but as Bernbach would have said, his unchanging need to guard against an unknown  visitors and their untested products is just as it strong as it always has been.

visitors and their untested products is just as it strong as it always has been.

Sometimes text is just part of the communication medium. And not the most important, but it’s interaction with what is going on around is what’s doing the work. A moving simple story of PTSD from a widow. Have your Kleenex ready.

When writing a case history for your organisation, you’ll find a narrative is a great way to reveal the moment of brilliance. All you have to do is ask: what were the circumstances that helped you think up the idea? The exact time, place, motivation, and question that provoked it. Very often just unpacking that exact moment of conception will create the excitement in the minds of your audience. And consequently an appreciation for the brilliance that went into it.

A good example of this is Michelle Mone’s moment in the toilet during a dinner dance, when she’s taking off an extremely uncomfortable bra. In that moment she decides to invent her Ultimo bra. But how do you do this in a video? You can’t recreate that without actors, sets and a high budget. So very often the best way to show a case history is to show the idea being executed.

So with video as a story telling medium, it’s the execution rather than the conception which makes for a good case history. In the following ideas, the film documents the idea being installed. Usually they preserve enough mystery to keep the viewer guessing. And whether it’s a footprint a keyboard or a phallus, doesn’t really matter. What counts is that there’s a twist to whatever you might have expected.

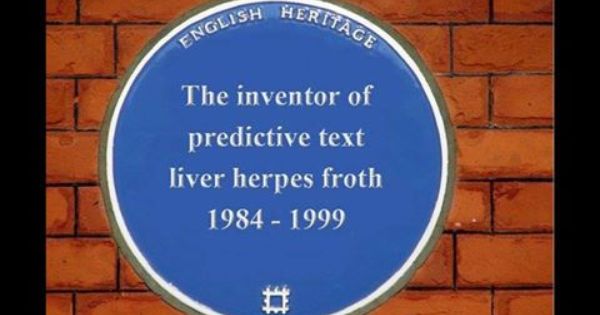

This neat little idea comes from building a symmetry between the transient text of a text message and the really permanent text of a blue plaque. The net result is a neat comment on just how annoying the wrong predictions are.

I’m always telling participants on the Copycourse that change is the key making a piece of writing interesting. Yet this cute little film keeps doing the opposite; It’s a story about keeping the bear in the same place.

So how come it’s so entertaining?

Well, for one the expectation for anyone who stands in a queue is to move forward. So the film turns our expectation of moving forward in a queue upside down. It plays with how we see the world.

And it keeps doing it in different ways.

All the while it’s saying something deeper about trying to get ahead: that it comes at the price of frustration.

As William Goldman said about screenwriting, give the audience what they expect, not in a way but not in the way that they expect it.

No wonder it got four thousand likes and counting.

Beneath all the flab on show there’s something quite subtle about this idea. The premise of being a Bollywood belly dancer is that you’ve got to enough fat to jiggle. So by celebrating belly dancing, you’re providing a neat piece of subliminal logic; namely other cultures are okay with a bit of extra flesh. It’s just the west where we’ve all gone anorexic.

Max Townshend uses story to convince people that frequencies far too high to hear, still make a difference to sound fidelity. Here he talks about high frequencies that go through the eyes, and cites ultrasonic welding tools causing factory workers to go deaf. The surprising elements in the story make it a credible and compelling piece of argument.

Getting an idea into a piece of communication transforms it.

I recently got asked to help out with a piece of communication that had gone wrong. A client had spent a lot of money filming some of their stakeholders and was trying to string it all together as a film.

The trouble was it didn’t work. Although the footage was, by and large well shot, the narrative was all over the place. It wasn’t clear whether some of the people we saw in silver framed photographs were alive or dead, and who exactly was doing what on whose behalf. But most of all, the reason it didn’t work was there was no idea, even slight idea to hold the whole thing together. Result: A budget halfway to six figures, and not much to show for it.

Ideas transform a piece of communication in several ways. One of these, I believe, is that getting an idea from a piece of communication often feels like receiving a gift. And a gift is an ideal way to begin a relationship. And just like we enjoy, almost anticipate, receiving a gift at the beginning of a personal relationship, and the same is true in the brand world. When we begin a relationship with an inanimate object or service we call a brand, we also expect some kind of gift; this is often given in the form of an idea.

Without an idea, it just feels a like a lecture. Now, how can I explain that to this client…

pre session task